Emblems in stone and wind: Chapter II

- David Steinberg דוד שטיינברג

- Aug 9, 2020

- 15 min read

Updated: May 2, 2025

Chapter II: Symbols of sovereignty in Jerusalem

The Ottoman Emblem on the Jerusalem District Heath Bureau building: photo ©Ranbar

This series of virtual tours aims to reference elements found in actual field trips across the country, with a special focus on Jerusalem. In this chapter, we explore historical symbols of sovereignty and secular governance. The symbols and flags of the ancient Israelite kingdoms are not available to us. Neither the Old Testament Kingdoms of Israel and Judah (circa 1000 BC to 586 BC) nor the Second Temple period (500 BC to 70 AD) have left us such symbols. The Stars of David and Solomon were later additions to Jewish culture. The menorah and holy vessels served as liturgical symbols for religious worship. If there were any state symbols, they have not survived. There is no known specific symbol for the Hasmonean kingdom or Herod's vassal state.

The Romans, 63 BC to 324 AD

The Roman symbols from that era are much more recognized. The Roman soldiers carried the "Vexillum," the legionary standard. When not engaged in battle, the Roman army was occupied with construction throughout the empire, including in this country, where they built roads, bridges, aqueducts, palaces, and fortifications. Upon completing these structures, their marks were inscribed on them or near their military camps. The legion emblems were carved in stone or clay. Two Roman legions were present in the area. The most renowned was the Tenth Legion Fretensis (of the Straits, Straits of Messina), which had defeated the Jewish revolt and was responsible for the destruction of Herod's temple. It also governed the land in subsequent centuries. The other was the Sixth Legion Ferrata. Numerous remains of both legions have been discovered. Their initials are etched on milestones and on memorial tablets known as Tabulae Ansate, found in various locations.

The vexillum, or legionary standard, was carried at the forefront of the Roman battalions alongside the eagle and the SPQR letters of Rome. Following this is a construction signature of the Sixth Legion Ferrata from the aqueduct in Caesarea. The inscription, discovered near the ancient city, dates back to the reign of Emperor Hadrian (130 AD) and is currently housed in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. This inscription, along with the next three, is on stone markers known as "tabula ansata." A tabula ansata features a surface with two "ears" extending from it, and these were also used as banners.

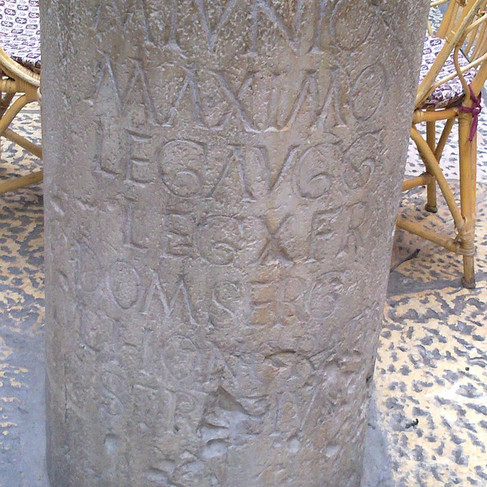

A milestone with the dedication of a soldier to the Tenth Legion Fretensis (can be seen in the fourth line of the text: the name of the Tenth Legion in initials: LEG X FRE.) The pillar is at the entrance to the Imperial Hotel, near the Jaffa Gate. The same signature appears in the tabula ansata at the Abu Ghosh Monastery, near Jerusalem.

The Byzantines, 324 AD to 638 AD

No specific governmental symbols from the Byzantine period have survived. Besides the crucifix and cross used in religious contexts, the empire's symbols remained unchanged during the early centuries AD, particularly in the Holy Land. The Byzantines considered themselves successors of the Roman Empire and retained its symbols. Some vexilloids incorporated Constantine's Greek letters XP (Chi-Rho, see the section about Christian symbols in Chapter I)), and it is believed that during this time, the Roman eagle evolved into a two-headed form. Ultimately, the emblem and banner of the 11th-century Palaeologus dynasty were used by the Empire until its fall in 1462.

The First Arab Period 638 AD to 1099 AD

The first Arab period, which included the rule of the Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid dynasties did not bring with it much regarding flags and emblems. Most of the flags may have carried inscriptions, but it is clear that the aversion of Muslims concerning figurative and symbolic expression did not contribute to the formation of national symbols at that time. The names of God, the Prophet, the Rashidun and quotations from the Qur'an constituted the expression of sovereignty over stone and flag.

The Crusaders 1099 to 1291

The Crusaders imported heraldry into this country - the lore of feudal family symbols - the visual symbolic language of European nobility. A systematic set of rules of form and color symbolizing origin and status. This visual language is the foundation from which the language of modern national flags evolved. It was developed in the Middle Ages, also here in the Holy land, starting in the 12th century, and some of the symbols created here were then brought over to Europe.

The Crusader states, from Edessa in northern Syria to the Holy Land were called in French "Outremer".

Map of the Middle East and the Crusader states. In 1135 the Crusader kingdom was at the peak of its power. The city of Jerusalem was taken over by Saladin as early as 1187, but the kingdom survived for another 100 years, along the coastal plain, with its capital in Acre. In 1291, the Egyptian Mamluks captured the last Crusader fortress and eliminated the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The emblem of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem is attributed to Godfrey of Bouillon, who was elected the first King of Jerusalem. He famously rejected the crown on the grounds that he would not bear a golden crown in the city where Jesus wore the crown of thorns.

He established a new emblem and chose a special cross for him and his kingdom, called ever-since the Jerusalem Cross: a cross potent surrounded by four crosslets. There are a few interpretations: Some claim these are the wounds of Jesus on the cross: the four wounds of the nails and the wound of the lance. Others claim that it is Jesus and the four evangelists. Either way, the uniqueness of the emblem and flag is in its colors. According to the first Law of Tincture in heraldry (Règle de contrariété des couleurs), metal should never be put on metal. Gold is represented as yellow and silver is represented as white, and there is little contrast between them. The other colors are green, azure, black, red and purple. Godfrey, however, sought to create an exception. "Because Jerusalem is the redemptive city of mankind, it deserves an exception: the two precious metals." This emblem was adopted as the emblem of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and is found, even today, on the blazons of several European royal and noble families, claiming the titular crown of the Holy Kingdom of Jerusalem which ceased to exist as early as 1291.

Arms and flag of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Moreover, many knights came to the Holy Land carrying their coats of arms and shields. Here, in the Holy Land, however, the Chivalrous Orders developed, which later returned to Europe with much power and money. We will mention four of them here.

The Crusader Chivalrous Orders

We tend to see them today as relics of the past, institutions which existed in a distant history. This is far from true. They are alive and kicking even today, even in Jerusalem. Due to the sensitivity of this matter among Jews, and especially among the Muslims, they tend to keep their visibility discreet, and engage mainly in ecumenical activities and charity.

There seems to be a contradiction between Christian monastic orders and military activity, as Christianity is bound to non-violence and turning the other cheek. Due to the fact that Christian pilgrims and travelers were attacked throughout their journey to the Holy Land, especially by bandits and pirates, a need had arisen to protect them. Therefore, the church allowed these monks to carry weapons and protect pilgrims, under strict moral rules. Thus, orders of warrior knights were created, who also defended the Crusader kingdom. When they were expelled from the Holy Land by the Muslims, they returned to Europe, maintaining their military might and economic assets as bankers. Some orders were accepted, others like the Knights Templar were brutally persecuted. In the late 19th century representatives of the surviving orders began to find their way back to the city.

The Knights Templar

The first and most famous orders is the "Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon" an order of warrior monks established in Jerusalem in 1119 to protect and defend European Catholics. The order was located on Temple Mount, where traditionally, the 'Templum Salomonis' is believed to have stood. Hence their name: Knights Templar. They kept a strictly modest and ascetic lifestyle, to the point that two knights rode on one horse, and that is famously represented on their seal. Their fate was harsh. They became very rich and gained enormous economic and political influence in Europe, before and after the Crusaders were expelled from the country. Philip IV, King of France, for complex reasons, liquidated the order and confiscated its property in a most brutal campaign and it was perpetually suppressed by Pope Clement V in 1312. Many members of the order were charged with various bizarre charges and brutally executed. This is what has happened in most European countries. In a few of them the Templars managed to survive.

The cross of the Order, brought by the Knights to Portugal, became a national symbol there, under the title "The Order of Jesus." The war flag of the Order and finally, two sides of the Order's seal: two knights on one horse and the Dome of the Rock emblem, under the title "Temple of Christ." I don't know of a place in the city where these symbols can be seen, but they are important in its history.

The Knights Hospitaller

As their name implies, they developed the first hospitals in the Holy Land for Christian pilgrims. Their first central hospital was in the Muristan area of the Old City, in what is now the Greek Market, near the German Lutheran Church of the Redeemer (Erlöserkirche). A hospital was probably already built in the Byzantine period and operated in one way or another during early Muslim rule. In 1060 a hospital for pilgrims was opened and in 1080, The blessed Gerard (Gerrardo Sasso) a lay priest, was appointed to run the hospital. With the Crusader occupation, the hospital grew and received financial support from the State. The priests began to accompany the pilgrims and thus gradually became another military order of knight-priests, with a strict moral code and rules. They became very powerful, both economically and politically and a turned into a formidable military force. With the fall of Jerusalem, they moved to Acre and with the fall of Acre in 1291, they established their center on the Island of Rhodes, where their influence is evident everywhere. From there they moved to the island of Malta, which they ruled for many years. They still maintain wealth and political influence and are now active throughout European countries.

In Jerusalem, there remains a living relic of their work: the St John of Jerusalem Eye Hospital. This hospital was established at the end of the 19th century by an English order called "The Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem". In the 19th century the hospital operated from what is now the Mount Zion Hotel near the Cinemateque, then their center moved to the Old City, where a cenotaph is located near the Muristan as a memorial to where the old hospital used to be, and finally a modern hospital was opened in Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem, operating to this day. There are more clinics around the West Bank and a new modern hospital in Hebron. There is also a German Johanniter Hospitz on the Via Dolorosa.

These are the international symbols of the Sovereign Order of the Hospitaller Knights: the State flag, of a simple white cross on a red background, the flag with a Malta cross on a red (sometimes the white Malta cross appears on a black background). And finally, the order's coat of arms.

The Old City memorial of the old eye hospital, located on Muristan street. The modern hospital in Sheikh Jarrah (second photo). The German Johanniter Hostel on Khankah alley in the Old City; The flag which is hoisted over the memorial, with the symbol of the Order of St. John and finally, the two emblems on the cenotaph.

The German Knights (Teutonic Order)

The German Order also began as a hospital by a pair of philanthropists, who founded it for German-speaking sick and wounded. It operated in the Muristan area and with the conquest of Jerusalem, was closed. The Order and the Hospital were re-established in Acre, in northern Israel, in 1192 and the German Knights have actively participated in the Crusades from the Third onwards. Their organizational and military center in the country was the Montfort Fortress in northern Galilee. They established a strong military and economic force, and with the expulsion of the Crusaders began to operate in many parts of Europe, developing independent entities there, especially in the regions of East Prussia and the Baltic countries. Their symbols are seen in Jerusalem, less from the time of the Crusaders and more due to the fact that the German-speaking powers Austria and Germany brought back the symbols to various places in the city in the late nineteenth century. In addition, their symbols inspire German national symbols to this day.

The black cross on a white shield worn by the German knights. Next, the cross of the head of the order, with the German Imperial Eagle of the Holy Roman Empire. This is the source of the modern German emblem. The imperial eagle emblem is engraved in stone over the arch on Muristan Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, passing into David Street. The symbol was embedded over the gate during the visit, in the late 19th century, of the German Kaiser. Finally, the ceremonial cross of the German Order, which inspired the Iron Crosses and the symbols of the German army and air force to this day.

The Austro-Hungarians

A mural in the Imperial Chapel at the Austrian Hostel, built in anticipation of the visit of Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1867. In the painting he arrives in Jerusalem accompanied by the chivalrous orders of the Middle Ages (on the left, with their emblems) and the peoples of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in traditional dress on the right. After all, as part of his Habsburg heritage, he was the king of Jerusalem, at least by title. This mural expresses the longing for the crusader heritage of the city. This hostel, built in 1855, was also intended to demonstrate the presence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was then an important player in the European arena. The Austrian flag still flies proudly over the roof of the hostel that now operates as a hotel in a wonderful vantage point familiar to many.

The Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem.

Of the all orders that were here in the Middle Ages, one has suddenly returned to charitable activities in Jerusalem after an absence of seven hundred years. This is the Military and Hospitaller Order of St. Lazarus (who Jesus had revived from the dead).

They are not recognized by the Vatican and are considered a self-styled private institution, but they gain support from some non-reigning European dynasties.

In the Middle Ages they split from mainstream Hospitallers and specified in the construction of special leper hospitals (Lazarets). They took part in the battles of the Crusader kingdom and retired to Acre after the conquest of Jerusalem by Saladin. After the fall of Acre, they returned to the town of Boigny in France. They have a connection to the French royal house even today (The claimant to the crown of France was recently the head of the order) and are connected to present-day European nobility, mostly ex-reigning. The Jerusalem Municipality allowed them to establish a charity here. There was a time when they tried to supply golf carts for the disabled tourists in the Old City. Theirs is a Green Maltese Cross. One can see their flag, hoisted on one of the roofs near Jaffa Gate. This is their new center, opened in 2017. They also support the Syriac Church in Jerusalem and the Greek Catholic Church.

The flag of the order is hoisted near the Jaffa Gate with the personal banner of the head of the order, the order's coat of arms and the typical cross.

The Ayyubids

The dates of this period overlap with the previous one, as it includes the conquest of Jerusalem in 1187 and the fall of Crusader Acre in 1291.

Again, during this period we witness reduced figurative expression with the Muslim reconquest of Jerusalem by Saladin al-Ayyubi, who gave his name to the dynasty of sultans who made Cairo their capital. In 1187 he expelled the Crusaders from Jerusalem, although they still ruled the coastal plain until 1291. Perhaps due to the Crusader influence or due to temporary loosening of the rules, the rulers of the Ayyubid dynasty and Mamluks who followed, allowed themselves some symbolism. There is verbal evidence that Salah a-Din sat under a golden canopy with a silver eagle, but no visual evidence remains. However, in Cairo fortress, which he strengthened and built, there is a remnant of an eagle relief of his time. This symbol has gained immense significance in Arab countries as "Saladin's eagle", and appears on dozens of Arab national and state flags, including those of Egypt and Palestine. The eagle in the fort is headless, probably as a result of a late-period islamic iconoclasm. In the twentieth century, Saladin's eagle was resurrected.

The figure of Saladin has already become a symbol in its own right in the modern age, and it is printed in full armor, on shirts sold in the streets of Jerusalem's Old City. The relief of the eagle in Cairo fortress (Photo: @MENAsymbolism), inspired the Egyptian and Palestinian emblems and more. I do not know of any other symbols from this period in the country.

The Mamluks 1260 to 1516

The first Mamluk General to rule Egypt was Baybars, who, along with his ally Qutuz, overthrew the Ayyubid dynasty. His most notable military success was defeating Hulagu Khan's Mongol army at the Battle of Ein Jalut in 1260, in what is now northern Israel. This victory also hastened the Crusaders' expulsion from the Holy Land by eliminating some of their final strongholds. Baybars adopted a heraldic emblem, possibly influenced by European traditions, featuring two "lions passant." Some researchers debate whether the emblem represents a lion or a leopard, but it is undoubtedly a large and formidable feline. He was a prolific builder, constructing the postal road between Cairo and Damascus. In the city of Lyd, a bridge was built that still serves the modern road at the city's northern entrance. On this bridge, he stamped his seal of the lions, which also decorates the Lions' Gate in Jerusalem.

The first picture is of the Jindas Bridge in Lyd, where the lions are depicted playing with a mouse, on either side of the dedication to the Beybars marking the year the bridge was built. The second picture is of the Lions' Gate, at the eastern entrance to the Old City, with two lion reliefs on either side of the gate, which may have possibly been placed there by the Ottoman builders of the city , almost three hundred years later.

The Mamluk rulers contributed enormously to Jerusalem's public architecture. One of the great builders was Emir Saif a-Din Tankiz, viceroy of Syria from 1312 to 1340, who built more than any other Mamluk in Jerusalem - madrasas, khans, baths and aqueducts. His family symbol was the cup, which can be seen at the entrance to the khan, named after him, in the cotton market.

The Ottoman Empire

The tuğrâ, the stylized signature of Suleiman the Magnificent, circa 1540

The Ottomans, like their Mamluk predecessors, were Muslims and utilized the crescent and star symbol more extensively. They also employed stylized Islamic calligraphy and maintained geometric and floral motifs for decoration. However, they introduced a new element in the realm of symbols: a stylized Sultan's signature that incorporated symbolic elements of the reigning Sultan's name. This symbol is known as the tuğrâ. With each new Sultan, the letters of his name would change, but the emblem's structure remained largely unchanged. The symbol experienced few alterations and was minted on numerous coins and found on Ottoman structures across the country. Below is the golden signature of Sultan Mahmud II on a red background. The signature of the penultimate Sultan, Abdulhamid II, is particularly prevalent in the Holy Land.

Sabil Abu Nabut in Jaffa, built in 1809. Above, the tuğrâ of Sultan Mahmoud II as emblem of the state, and below it the personal emblem of Jaffa's governor, Muhammad Aga.

The walls of Jerusalem were constructed under the direction of Suleiman the Magnificent in 1538. Within these walls, there are numerous decorated stone roundels, some featuring the "Star of David." However, these are not symbols; rather, they are geometric and floral decorative elements without any symbolic significance.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire began to engage more with the West. In 1882, Sultan Abdul Hamid II was asked to provide a symbol to represent the State in Europe. Up until that point, the empire did not have an official emblem. Consequently, they designed a symbol in the European style, adhering to the Islamic guidelines regarding figurative imagery. While the tuğrâ is part of the emblem, it features only inanimate objects.such

as symbols of military strength, flowers representing tolerance, scales symbolizing justice, and a cornucopia, alongside a green flag of the Islamic Caliphate and a red flag of the Turkish Empire. The engraved coat of arms is carved in stone on various buildings throughout the country.

The complete coat of arms at the base of the clock tower in Acre, near Khan al-Umdan, was constructed in 1906 to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of Abdulhamid II's ascension to the throne. This symbol is engraved in marble. Another impressive emblem can be found on the façade of the former municipal hospital on Jaffa Street in West Jerusalem, which is now the District Health Bureau.

The British Mandate 1918 to 1948

The British received a mandate, a temporary control, over an Ottoman province they had taken over, to establish constitutional and institutional foundations for this part of the empire, which, according to international agreements and political commitments, was meant to become an independent state (Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Balfour Declaration, Sharifian Solution). It was not a British crown colony nor a region where British immigrants had settled (such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Kenya). In this case, the land was promised to both the Jews and the local Arab population at the same time.

Given the immediate hostility between Jews and Arabs, reaching any agreement was impossible, especially regarding symbols. The British found themselves in a difficult position, caught between their conflicting promises to both sides.

The Red Ensign for the merchant fleet and the governor general standard.

Thus, there was neither a colonial flag nor a naval flag. The Ensigns, typically altered with a local emblem in all British territories, were marked only with the inscription "Palestine" in English here, and there were more theoretical designs than actual flags. They were rarely used, possibly on merchant ships. Common British flags, such as the plain Union Jack and Red Ensign, were generally used. The state emblem remained the British Arms, reflecting the style of the period. Notably, two impressive official coats of arms, carved in wood, were located in the Government House and the high court. Remarkably, these have survived!

Their current locations are intriguing. One was taken from Government House when it was in the demilitarized zone between Israel and Jordan, becoming the center for UN representatives in the country, and is now housed in the Anglican Church of St. George on Nablus Road, in East Jerusalem, where it remains on display today. It was placed at the church on May 14, 1948. The second, likely from the Supreme Court of the Mandate, is located in the new Supreme Court Building in Jerusalem, where it is currently exhibited.

This concludes the chapter on political symbols of the past. I hope you found it enjoyable. These locations can be included in actual tours.

I invite you to read the final chapter of this series on symbols from both sides of the current conflict: the Israeli and the Palestinian.

Comments